What Is the Taxonomic Category Between Family and Species

Taxonomy is the science of describing, naming, and classifying living and extinct organisms (the term is likewise employed in a wider sense to refer to the classification of all things, including inanimate objects, places and events, or to the principles underlying the classification of things). The term taxonomy is derived from the Greek taxis ("arrangement;" from the verb tassein, meaning "to classify") and nomos ("constabulary" or "science," such as used in "economic system").

An of import science, taxonomy is basic to all biological disciplines, since each requires the right names and descriptions of the organisms existence studied. Even so, taxonomy is also dependent on the information provided by other disciplines, such as genetics, physiology, ecology, and anatomy.

Naming, describing, and classifying living organisms is a natural and integral activeness of humans. Without such knowledge, it would be difficult to communicate, let alone signal to others what constitute is poisonous, what plant is edible, and so forth. The volume of Genesis in the Bible references the naming of living things every bit i of the first activities of humanity. Some further feel that, beyond naming and describing, the human mind naturally organizes its knowledge of the earth into systems.

In the later decades of the twentieth century, cladistics, an alternate approach to biological nomenclature, has grown from an idea to an all-encompassing program exerting powerful influence in classification and challenging Linnaean conventions of naming.

Contents

- i Taxonomy, systematics, and alpha taxonomy: Defining terms

- 2 Universal codes

- 3 Scientific or biological classification

- 3.one Domain and Kingdom systems

- 3.ii Examples

- 3.three Grouping suffixes

- four Historical developments

- 4.ane Linnaeus

- 4.2 Classification after Linnaeus

- v References

- six Credits

Taxonomy, systematics, and blastoff taxonomy: Defining terms

For a long time, the term taxonomy was unambiguous and used for the nomenclature of living and once-living organisms, and the principles, rules and procedures employed in such nomenclature. This use of the term is sometimes referred to as "biological classification" or "scientific classification." Beyond classification, the field of study or science of taxonomy historically included the discovering, naming, and describing of organisms.

Over time, however, the give-and-take taxonomy has come to take on a broader meaning, referring to the nomenclature of things, or the principles underlying the nomenclature. Virtually anything may be classified according to some taxonomic scheme, such every bit stellar and galactic classifications, or classifications of events and places.

An administrative definition of taxonomy (every bit used in biology) is offered by Systematics Calendar 2000: Charting the Biosphere (SA2000), a global initiative to notice, describe, and allocate the world's species. Launched by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists, the Guild of Systematic Biologists, and the Willi Hennig Society, and in cooperation with the Association of Systematic Collections, SA2000 defines taxonomy equally "the science of discovering, describing, and classifying species or groups of species."

The Select Commission on Science and Technology of the Great britain Parliament also offers an official definition for taxonomy: "We use taxonomy to refer to the activities of naming and classifying organisms, equally well as producing publications detailing all known members of a item group of living things."

The term "systematics" (or "systematic biological science") is sometimes used interchangeably with the term taxonomy. The words have a similar history and like meanings: Over time these have been used as synonyms, equally overlapping, or as completely complementary.

In general, however, the term systematics includes an attribute of phylogenetic analysis (the study of evolutionary relatedness amidst various groups of organisms). That is, it deals not simply with discovering, describing, naming, and classifying living things, only also with investigating the evolutionary relationship betwixt taxa (a taxonomic group of any rank, such as sub-species, species, family unit, genus, and so on), peculiarly at the higher levels. Thus, according to this perspective, systematics non only includes the traditional activities of taxonomy, but also the investigation of evolutionary relationships, variation, speciation, and then along. Still, there remain disagreements on the technical differences between the two terms—taxonomy and systematics—and they are oftentimes used interchangeably.

"Blastoff taxonomy" is a sub-discipline of taxonomy and is concerned with describing new species, and defining boundaries between species. Activities of blastoff taxonomists include finding new species, preparing species descriptions, developing keys for identification, and cataloging the species.

"Beta taxonomy" is another sub-field of study and deals with the arrangement of species into a natural system of nomenclature.

Universal codes

Codes have been created to provide a universal and precise system of rules for the taxonomic classification of plants, animals, and bacteria. The International Lawmaking of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN) is the set of rules and recommendations dealing with the formal botanical names that are given to plants. Its intent is that each taxonomic grouping ("taxon", plural "taxa") of plants has only 1 correct name, accustomed worldwide. The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a set of rules in zoology to provide the maximum universality and continuity in classifying animals according to taxonomic judgment. The International Code of Classification of Leaner (ICNB) governs the scientific names for leaner.

Scientific or biological classification

Biologists grouping and categorize extinct and living species of organisms by applying the procedures of Scientific classification or biological classification. Modern classification has its roots in the system of Carolus Linnaeus, who grouped species according to shared physical characteristics. Groupings accept been revised since Linnaeus to reverberate the Darwinian principle of common descent. Molecular systematics, which uses genomic Dna assay, has driven many contempo revisions and is likely to continue to do then.

Scientific classifications, or taxonomies, are frequently hierarchical in construction. Mathematically, a hierarchical taxonomy is a tree structure of classifications for a given fix of objects. At the top of this structure is a single nomenclature, the root node, which is a category that applies to all objects in the tree structure. Nodes below this root are more specific classifications or categories that apply to subsets of the total set of classified objects.

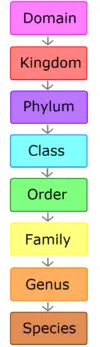

And then, for instance, in common schemes of scientific classification of organisms, the root category is "Organism." Equally all living things belong to this category, it is commonly implied rather than stated explicitly. Below the implied root category of organism are the following:

- Domain

- Kingdom

- Phylum

- Class

- Social club

- Family unit

- Genus

- Species

Various other ranks are sometimes inserted, such as subclass and superfamily.

Carolus Linnaeus established the scheme of using Latin generic and specific names in the mid-eighteenth century (see species); subsequently biologists extensively revised his work.

Domain and Kingdom systems

At the top of the taxonomic classification of organisms, one can find either Domain or Kingdom.

For 2 centuries, from the mid-eighteenth century until the mid-twentieth century, organisms were more often than not considered to belong to one of ii kingdoms, Plantae (plants, including leaner) or Animalia (animals, including protozoa). This system, proposed by Carolus Linnaeus in the mid-eighteenth century, had obvious difficulties, including the trouble of placing fungi, protists, and prokaryotes. At that place are single-celled organisms that fall between the ii categories, such every bit Euglena, that can photosynthesize food from sunlight and, yet, feed by consuming organic matter.

In 1969, American ecologist Robert H. Whittaker proposed a organisation with five kingdoms: Monera (prokaryotes—bacteria and blue-greenish algae), Protista (unicellular, multicellular, and colonial protists), Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia. This organization was widely used for three decades, and remains pop today.

More recently, the "domain," a nomenclature level higher than kingdom, has been devised. Also chosen a "Superregnum" or "Superkingdom," domain is the top-level grouping of organisms in scientific classification. One of the reasons such a classification has been developed is because enquiry has revealed the unique nature of anaerobic leaner (chosen Archaeobacteria, or simply Archaea). These "living fossils" are genetically and metabolically very dissimilar from oxygen-breathing organisms. Various numbers of Kingdoms are recognized under the domain category.

In the three-domain system, which was introduced past Carl Woese in 1990, the three groupings are: Archaea; Leaner; and Eukaryota. This scheme emphasizes the separation of prokaryotes into ii groups, the Bacteria (originally labelled Eubacteria) and the Archaea (originally labeled Archaebacteria).

In some classifications, authorities keep the kingdom every bit the higher-level classification, merely recognize a sixth kingdom, the Archaebacteria.

Coexisting with these schemes is yet another scheme that divides living organisms into the ii main categories (empires) of prokaryote (cells that lack a Nucleus: Leaner so on) and eukaryote (cells that have a nucleus and membrane-spring organelles: Animals, plants, fungi, and protists).

In summary, today there are several competing height classifications of life:

- The iii-domain arrangement of Carl Woese, with meridian-level groupings of Archaea, Eubacteria, and Eukaryota domains

- The two-empire system, with top-level groupings of Prokaryota (or Monera) and Eukaryota empires

- The five-kingdom organization with top-level groupings of Monera, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia

- The six-kingdom arrangement with top-level groupings of Archaebacteria, Monera, Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia

Overall, the majority of biologists take the domain system, merely a large minority uses the five-kingdom method. A pocket-size minority of scientists adds Archaea or Archaebacteria as a sixth kingdom but do non accept the domain method.

Examples

The usual classifications of five representative species follow: the fruit fly and so familiar in genetics laboratories (Drosophila melanogaster); humans (Man sapiens); the peas used by Gregor Mendel in his discovery of genetics (Pisum sativum); the fly agaric mushroom Amanita muscaria; and the bacterium Escherichia coli. The viii major ranks are given in bold; a choice of minor ranks is given every bit well.

| Rank | Fruit wing | Human | Pea | Fly Agaric | E. coli |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Bacteria |

| Kingdom | Animalia | Animalia | Plantae | Fungi | Monera |

| Phylum or Partitioning | Arthropoda | Chordata | Magnoliophyta | Basidiomycota | Eubacteria |

| Subphylum or subdivision | Hexapoda | Vertebrata | Magnoliophytina | Hymenomycotina | |

| Class | Insecta | Mammalia | Magnoliopsida | Homobasidiomycetae | Proteobacteria |

| Bracket | Pterygota | Placentalia | Magnoliidae | Hymenomycetes | |

| Guild | Diptera | Primates | Fabales | Agaricales | Enterobacteriales |

| Suborder | Brachycera | Haplorrhini | Fabineae | Agaricineae | |

| Family unit | Drosophilidae | Hominidae | Fabaceae | Amanitaceae | Enterobacteriaceae |

| Subfamily | Drosophilinae | Homininae | Faboideae | Amanitoideae | |

| Genus | Drosophila | Homo | Pisum | Amanita | Escherichia |

| Species | D. melanogaster | H. sapiens | P. sativum | A. muscaria | E. coli |

Notes:

- Botanists and mycologists apply systematic naming conventions for taxa higher than genus by combining the Latin stem of the type genus for that taxon with a standard ending feature of the particular rank. (See below for a list of standard endings.) For example, the rose family Rosaceae is named after the stem "Ros-" of the type genus Rosa plus the standard ending "-aceae" for a family.

- Zoologists utilise similar conventions for college taxa, but only up to the rank of superfamily.

- Higher taxa and especially intermediate taxa are prone to revision every bit new information near relationships is discovered. For instance, the traditional nomenclature of primates (grade Mammalia—bracket Theria—infraclass Eutheria—society Primates) is challenged by new classifications such as McKenna and Bell (course Mammalia—subclass Theriformes— infraclass Holotheria—order Primates). These differences arise because at that place are only a small number of ranks available and a big number of proposed branching points in the fossil record.

- Within species, further units may be recognized. Animals may be classified into subspecies (for example, Homo sapiens sapiens, mod humans). Plants may be classified into subspecies (for example, Pisum sativum subsp. sativum, the garden pea) or varieties (for example, Pisum sativum var. macrocarpon, snowfall pea), with cultivated plants getting a cultivar name (for example, Pisum sativum var. macrocarpon "Snowbird"). Bacteria may be classified by strains (for example Escherichia coli O157:H7, a strain that tin cause food poisoning).

Grouping suffixes

Taxa above the genus level are often given names derived from the Latin (or Latinized) stalk of the type genus, plus a standard suffix. The suffixes used to grade these names depend on the kingdom, and sometimes the phylum and form, as set up out in the table below.

| Rank | Plants | Algae | Fungi | Animals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division/Phylum | -phyta | -mycota | ||

| Subdivision/Subphylum | -phytina | -mycotina | ||

| Class | -opsida | -phyceae | -mycetes | |

| Subclass | -idae | -phycidae | -mycetidae | |

| Superorder | -anae | |||

| Order | -ales | |||

| Suborder | -ineae | |||

| Infraorder | -aria | |||

| Superfamily | -acea | -oidea | ||

| Family | -aceae | -idae | ||

| Subfamily | -oideae | -inae | ||

| Tribe | -eae | -ini | ||

| Subtribe | -inae | -ina | ||

Notes

- The stalk of a word may not be straightforward to deduce from the nominative form as information technology appears in the name of the genus. For example, Latin "homo" (man) has stem "homin-", thus Hominidae, not "Homidae".

- For animals, there are standard suffixes for taxa only upwards to the rank of superfamily (ICZN commodity 27.2).

Historical developments

Classification of organisms is a natural activity of humans and may be the oldest scientific discipline, every bit humans needed to allocate plants equally edible or poisonous, snakes and other animals as dangerous or harmless, and and then forth.

The earliest known arrangement of classifying forms of life comes from the Greek philosopher Aristotle, who classified animals based on their ways of transportation (air, land, or water), and into those that have red claret and have alive births and those that do non. Aristotle divided plants into trees, shrubs, and herbs (although his writings on plants take been lost).

In 1172, Ibn Rushd (Averroes), who was a approximate (Qadi) in Seville, translated and abridged Aristotle'south book de Anima (On the Soul) into Arabic. His original commentary is now lost, but its translation into Latin by Michael Scot survives.

An of import accelerate was fabricated by the Swiss professor, Conrad von Gesner (1516–1565). Gesner'south piece of work was a critical compilation of life known at the time.

The exploration of parts of the New World side by side brought to manus descriptions and specimens of many novel forms of animal life. In the latter part of the sixteenth century and the start of the seventeenth, conscientious study of animals commenced, which, directed start to familiar kinds, was gradually extended until it formed a sufficient torso of knowledge to serve every bit an anatomical basis for classification. Advances in using this knowledge to classify living beings bear a debt to the research of medical anatomists, such every bit Hieronymus Fabricius (1537 – 1619), Petrus Severinus (1580 – 1656), William Harvey (1578 – 1657), and Edward Tyson (1649 – 1708). Advances in classification due to the piece of work of entomologists and the first microscopists is due to the inquiry of people similar Marcello Malpighi (1628 – 1694), Jan Swammerdam (1637 – 1680), and Robert Hooke (1635 – 1702).

John Ray (1627 – 1705) was an English naturalist who published important works on plants, animals, and natural theology. The approach he took to the nomenclature of plants in his Historia Plantarum was an important step towards modern taxonomy. Ray rejected the system of dichotomous division by which species were classified according to a pre-conceived, either/or type system, and instead classified plants according to similarities and differences that emerged from observation.

Linnaeus

Two years after John Ray's death, Carolus Linnaeus (1707–1778) was born. His great work, the Systema Naturae, ran through twelve editions during his lifetime (1st ed. 1735). In this work nature was divided into three realms: mineral, vegetable, and animal. Linnaeus used 4 ranks: course, order, genus, and species. He consciously based his system of nomenclature and classification on what he knew of Aristotle (Hull 1988).

Linnaeus is all-time known for his introduction of the method nevertheless used to codify the scientific name of every species. Before Linnaeus, long, many-worded names had been used, only equally these names gave a description of the species, they were not stock-still. By consistently using a two-word Latin proper name—the genus name followed by the specific epithet—Linnaeus separated nomenclature from taxonomy. This convention for naming species is referred to every bit binomial nomenclature.

Nomenclature after Linnaeus

Some major developments in the system of taxonomy since Linnaeus were the development of unlike ranks for organisms and codes for nomenclature (see Domain and Kingdom systems, and Universal Codes above), and the inclusion of Darwinian concepts in taxonomy.

According to Hull (1988), "in its heyday, biological systematics was the queen of the sciences, rivaling physics." Lindroth (1983) referenced information technology as the "most lovable of the sciences." But at the time of Darwin, taxonomy was not held in such high regard as information technology was earlier. It gained new prominence with the publication of Darwin's The Origin of Species, and particularly since the Modern Synthesis. Since and then, although there take been, and go on to be, debates in the scientific customs over the usefulness of phylogeny in biological classification, it is generally accepted by taxonomists today that classification of organisms should reverberate or correspond phylogeny, via the Darwinian principle of common descent.

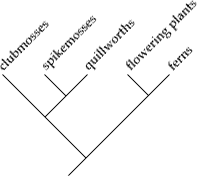

A vertical orientation yields a cladogram reminiscent of a tree.

Taxonomy remains a dynamic scientific discipline, with developing trends, diversity of opinions, and clashing doctrines. Ii of these competing groups that formed in the 1950s and 1960s were the pheneticists and cladists.

Begun in the 1950s, the pheneticists prioritized quantitative or numerical assay and the recognition of similar characteristics among organisms over the alternative of speculating nigh process and making classifications based on evolutionary descent or phylogeny.

Cladistic taxonomy or cladism groups organisms by evolutionary relationships, and arranges taxa in an evolutionary tree. Most mod systems of biological nomenclature are based on cladistic analysis. Cladistics is the most prominent of several taxonomic systems, which also include approaches that tend to rely on fundamental characters (such as the traditional approach of evolutionary systematics, as advocated by G. G. Simpson and E. Mayr). Willi Hennig (1913-1976) is widely regarded every bit the founder of cladistics.

References

ISBN links back up NWE through referral fees

- Hull, D. L. 1988. Science as a Procedure: An Evolutionary Account of the Social and Conceptional Development of Science. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Printing.

- Lindroth, S. 1983. The two faces of Linnaeus. In Linnaeus, the Man and his Work (Ed. T. Frangsmyr) one-62. Berkeley: Academy of California Printing.

Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Taxonomy

0 Response to "What Is the Taxonomic Category Between Family and Species"

Post a Comment